Mathematics can be challenging for learners everywhere and some problems push thinking even further.

We’ve gathered five of the trickiest mathematics questions from around the world to test your reasoning skills and spark engaging classroom discussion.

Solutions are included at the end (but try not to peek!). And if you’re ready for an extra challenge, there’s a bonus question waiting for you too.

Before we dive in, a quick announcement: World Maths Day, the world’s largest celebration of mathematics, returns on 25 March 2026.

Each year, millions of students aged 5–18 participate in friendly, fast-paced Live Mathletics challenges – all completely free and open to schools and learners everywhere. Learn how your students can get involved!

Ready? Here are the questions…

1. People on a Train

Country of origin: England

This problem first gained attention when it appeared in a primary school assessment for learners aged 6–7. It quickly went viral because even many adults found themselves double-checking their reasoning.

The question:

There were some people on a train.

19 people get off the train at the first stop.

17 people get on the train.

Now there are 63 people on the train.

How many people were on the train to begin with?

2. You’ll Never Forget Cheryl’s Birthday

Country of origin: Singapore

Logic-based problems frequently appear in mathematics competitions, but this particular question from the 2015 Singapore and Asian Schools Math Olympiad (designed for students aged 14–15)captured worldwide attention for its unexpected complexity.

The question:

Albert and Bernard have just become friends with Cheryl, and they want to know when her birthday is.

Cheryl gives them a list of 10 possible dates:

- May 15, May 16, May 19

- June 17, June 18

- July 14, July 16

- August 14, August 15, August 17

Cheryl then tells Albert the month, and Bernard the day of her birthday.

Albert: “I don’t know when Cheryl’s birthday is, but I know that Bernard doesn’t know either.”

Bernard: “At first I didn’t know when Cheryl’s birthday was, but now I know.”

Albert: “Then I know it too.”

So, when is Cheryl’s birthday?

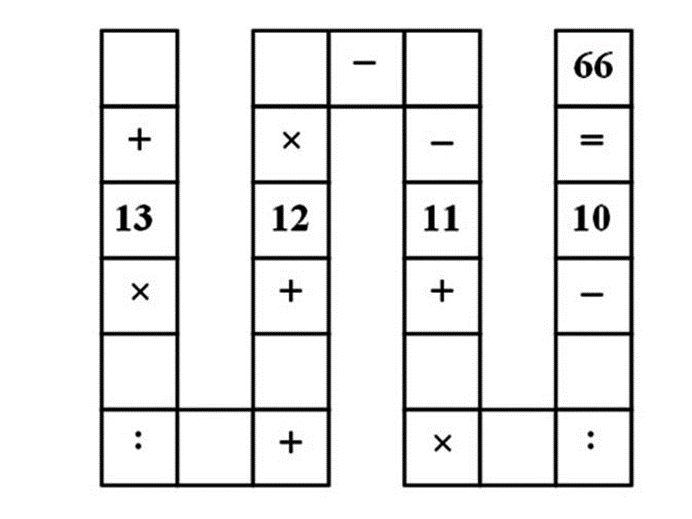

3. Taming the Snake

Country of origin: Vietnam

This puzzle is both challenging and time-consumingand surprisingly, it was designed for Year 3 learners (around age 8) in Vietnam, according to VNExpress.

The puzzle:

Use the digits 1 to 9, each exactly once, to fill in the boxes so that the entire expression equals 66.

Read the expression strictly from left to right as you solve it.

Note: In this puzzle, the boxes containing a colon (:) represent division.

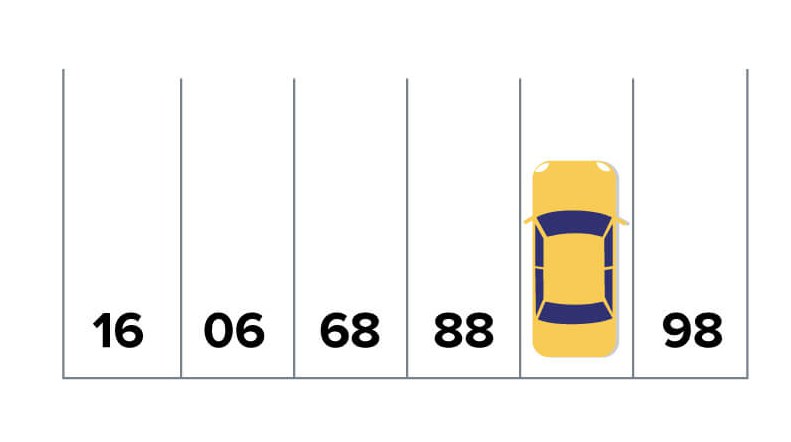

4. Remember Where You Parked Your Car

Country of origin: Hong Kong

This puzzle circulated for years but gained renewed attention when it appeared on an entrance assessment for young learners in Hong Kong.

Students around six years old were expected to solve it in under 20 seconds.

The question:

What number is the car parked on?

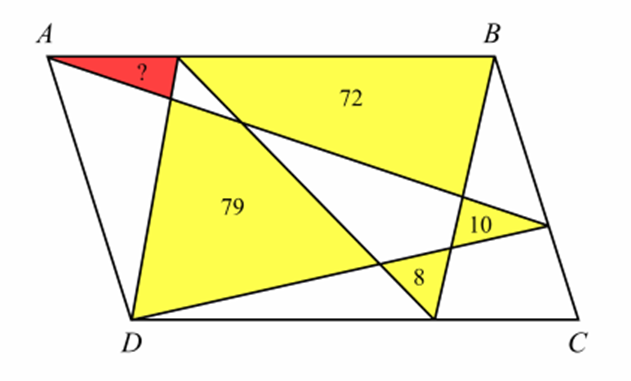

5. The Red Triangle

Country of origin: China

This geometry problem was reportedly used in China to identify high-achieving Year 5/fifth-grade learners (around ages 10–11). Many students were able to solve it in under a minute, making it a favourite example of visual reasoning and spatial problem-solving

The question:

ABCD is a parallelogram. In the diagram, the areas of the yellow regions are 8, 10, 72, and 79.

Find the area of the red triangle.

Note: The diagram is not drawn to scale.

Bonus challenge: Helen and Ivan’s Coins

Country of origin: Singapore

This two-part problem gained attention in 2021 when it appeared in Singapore’s Primary School Leaving Examination. Designed for 12-year-old learners, it required students to apply both numerical reasoning and knowledge of mass.

The questions:

Helen and Ivan each had the same number of coins.

- Helen had a number of 50-cent coins and 64 20-cent coins. Together, these coins had a mass of 1.134 kg.

- Ivan had a number of 50-cent coins and 104 20-cent coins.

(a) Who has more money in coins, and by how much?

(b) Given that each 50-cent coin is 2.7 g heavier than a 20-cent coin, what is the total mass of Ivan’s coins in kilograms?

Did you solve these tricky mathematics questions?

Some of these problems require real persistence and flexible thinking – so if you found yourself pausing along the way, you’re in good company.

If you’re an educator looking to build students’ confidence with problem-solving and mathematical reasoning, consider using a high-quality mathematics resource that supports logical thinking, strategic approaches, and deeper understanding.

Mathletics offers more than 700 problem-solving and reasoning questions designed to strengthen mathematical thinking and challenge learners at every level.

Now let’s take a look at the solutions…

Question 1: Answer – People on a Train

Getting off the train is represented by –19 and getting on is represented by +17.

-19 + 17 = –2, meaning there was a net loss of two people between the original number and the final number.

Since there are 63 people on the train now, the original number must have been:

63 + 2 = 65 people.

Question 2: Answer – Cheryl’s Birthday

This problem is solved by carefully applying logical elimination.

Given:

- Albert is told the month.

- Bernard is told the day.

Step 1: Albert’s first statement

Albert: “I don’t know when Cheryl’s birthday is, but I know that Bernard doesn’t know either.”

For Albert to be certain that Bernard cannot know the birthday, the day cannot be one that appears only once in the list.

Days that appear once: 18 and 19.

So, we eliminate the dates:

- May 19

- June 18

Albert can only be sure Bernard doesn’t know if the month he was told is not May or June.

So, we eliminate all dates in:

- May

- June

Remaining dates:

July 14, July 16, August 14, August 15, August 17

Step 2: Bernard’s statement

Bernard: “At first I didn’t know when Cheryl’s birthday was, but now I know.”

If Bernard were told 14, he still wouldn’t know the month (it appears in both July and August).

So, 14 is eliminated.

Remaining dates:

July 16, August 15, August 17

Step 3: Albert’s final statement

Albert: “Then I also know when Cheryl’s birthday is.”

If Albert had heard August, he would still have two possibilities.

So, he must have heard July.

Final answer: July 16.

Question 3: Answer – Taming the Snake

This puzzle challenges learners to use digits 1–9 exactly once to make an expression equal 66, working strictly left to right.

There are 9! (362,880) possible arrangements, so logical reasoning is more efficient than random trial-and-error.

One valid solution is:

9 + (13 × 4 ÷ 8) + 5 + (12 × 6) – 7 – 11 + (1 × 3 ÷ 2) – 10 = 66

Because addition and multiplication are commutative, swapping numbers within those operations can generate additional correct arrangements.

There are 136 valid solutions in total.

Question 4: Answer – Parking Space

The key insight is that the puzzle is not mathematical.

Turn the diagram upside down and the numbers form a simple sequence.

The car is parked in spot 87.

Question 5: Answer – The Red Triangle

Although the diagram appears complex, it can be solved using relationships between parallelogram and triangle areas.

Using area relationships within the parallelogram:

79 + 10 – 72 – 8 = 9

So, the red triangle’s area is 9.

This works because a triangle within a parallelogram, drawn with its base on one side and height to the opposite side, always has half the area of a corresponding parallelogram section.

Identifying pairs of such triangles reveals the needed relationships to compute the missing area.

Question 6 (a): Answer – Who Has More Money?

Helen and Ivan have the same number of coins.

- Ivan has 40 more 20-cent coins than Helen.

- Therefore, Helen must have 40 more 50-cent coins to keep the total number of coins equal.

Compare value differences:

20-cent coins:

Helen has 40 fewer → 40 × 0.20 = –$8

50-cent coins:

Helen has 40 more → 40 × 0.50 = +$20

Net difference:

20 – 8 = $12

Helen has $12 more than Ivan.

Question 6 (b): Answer – Mass of Ivan’s Coins

Helen’s coins weigh 1.134 kg.

Each 50-cent coin is 2.7 g heavier than each 20-cent coin.

Since Ivan has 40 fewer 50-cent coins and 40 more 20-cent coins, his coins weigh:

40 × 2.7 g = 108 g less than Helen’s.

Convert and subtract:

1134 g – 108 g = 1026 g

= 1.026 kg